LONDON TIMES

Victoria and Albert Museum, Medieval Collection

Except for, perhaps, the Tower of London and Westminster Abbey, one rarely thinks of London as a place that reflects its medieval roots, the way that Paris, for example, does in the Marais area, or, of course, with Notre Dame. This forgetting of London’s medieval past is not surprising, given that so much of the older neighborhoods of London were destroyed during the Great Fire of London of 1666, and, more recently, by the bombings during World War II. As a result, a good deal of medieval London was either totally recreated in the 17th century (as the Gothic St. Paul Cathedral was replaced by Christopher Wren’s neo-classical building) or reconstructed in large part during the 20th century (Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament).

http://www.westminster-abbey.org/our-history/war-damage

http://www.westminster-abbey.org/our-history/war-damage

London’s property is, of course, too valuable to simply skirt around; instead, people either simply rebuilt, or built over, London’s past. This layering of and over the past is one reason that this Hales Group did not wander as much as most of the previous ones have, for we were interested in ways in which one city can encaspsulate so heterogeneous, layered time and space. For me, this experience recalled the readings that I paired for our group: Micael Vaughn’s article, “The Three Advents of the Secunda Pastorum” and Neil Gaiman’s novel, Neverwhere. Vaughan’s article considers how the fourteenth century play, the Secunda Pastorum (also known as The Second Shepherd’s Play), reflects three different notions of time that medieval citizens inhabited simultaneously. As Vaughan notes, this play about the nativity of Jesus begins with historical time–with a recognizably fourteenth century shepherd grumbling about how “these weders (this weather) are cold” and how his “fingers are chappyd”, even as another shepherd complains about how they are “poore” and how they are subjected to nagging wives, . At the same time, the play exists in typological time, as, soon thereafter, these fourteenth shepherds become the shepherds who experience Jesus’s birth–reminding us of the Christian calendar, in which Jesus is born again every Christmas. Finally, there is apocalpytic time–a reminder of the end of days to come and the Last Judgement, emblematized ironically by the mischievous shepherd Max, who steals a lamb, then, in a parody of Jesus’s birth, pretends that the lamb is his newborn babe; he is then brought to a parodic Last Judgement, as he is tossed in a blanket: the anxieties of doomsday are turned into reconciliation and forgiveness of a fellow shepherd.

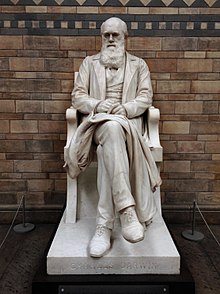

Where Vaughn considered how heterogeneous concepts of time inhabit the same belief system, Gaiman is more interested in archaeological time–in the way that London’s past continues to exist, literally, in its depth, as, over time, newer parts of London have been rebuilt over older parts. Gaiman imagines London’s past as co-existing with its present by creating a story focused on underground inhabitants who have been ejected by London’s present capitalist structures. As our visiting professor Priyanka Jacob noticed, for Gaiman, much of this heterogeneous past is, in fact, focused on Victorian London–particularly Dickensian London, with its Gothic, ragged inhabitants, although Gaiman does also suggest an earlier governmental of church and vassalage, embodied by the Black friars and a king, even as, in his novel, Gaiman clearly bemoans how contemporary Londoners–too often focused on getting and spending and building big gleaming buildings–have forgotten about their pasts, which explains why the denizens of underground London are simply invisible to them.

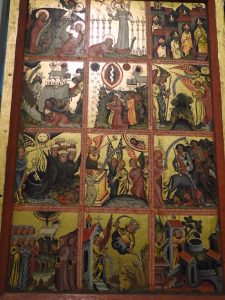

A few moments of our trip reminded me of London’s layerings of time For me, perhaps the most salient reminder of the readings was a German late fourteenth century altarpiece depicting the apocalypse that I encountered in my spinoff from the Natural History museum visit (itself a creation of 19th century notions of the medieval)–a trip to the museum next door, the Victoria and Albert Musuem.

The panel depicts, in startling ways, scenes from the Book of Revelations, scenes which clearly are meant to lift viewers away from contemplation of the mundane to consider the horrors and hopes in the final days of the world.In contrast, this early medieval (5th century) panel depicts an entirely different idea of medieval time, harking back as it does to Roman time (about which Monica has already commented) and to a mundane moment by a fountain, frozen in time.

But London’s attempt to hold on to its past by recreating it was an equally fascinating part of the visit, perhaps nowhere more so than in the New Globe Theater, built pretty much where the first Globe Theater was built.

I admit to many misgivings about this project. For one thing, it fetishizes the Globe Theater as the main place for Shakespearean productions, despite the fact that Shakespeare’s plays were performed elsewhere (mainly at a theater called “The Theater”) from 1589 to 1599–when the Globe Theater was built; it also ignores that Shakespeare’s plays, during his lifetime, were presented in private theaters and in the Elizabethan and Jacobean courts. And I wondered–and still wonder–about the Disneyesque quality of rebuilding of the Globe Theater by a Hollywood actor producer–although one who spent a good deal of his life in England, after fleeing the blacklist in Hollywood. As Marjorie Garber has noted (in her article “Shakespeare as Fetish), it seems all too much like an attempt to capture a fantasy of “Merrie Olde England, ” as if we could recreate and inhabit a time before electricity, cars, and capitalist democracy. I found some of the efforts to be authentic particularly problematic. There’s electricity all over the place (see the photo below), but they decided to be authentic by building in many of the bad sightlines from the original Globe. I also felt quite bad for some of the audience; during the show, one older, seated, audience member fainted and had to be taken out, while one of the younger groundling spectators had to be escorted out for the same reason. I’m not sure that’s the kind of authentic experience we really want to duplicate. Nonetheless, the production of King Lear we saw was riveting and searing, and, although the sound of the (non-Shakesperaean) tourist helicopters roaming above was distracting, there was something magnificent about watching a play while the open evening air is above you and the night slowly unfolds its stars.

And the atmosphere after the play, as people slowly sidled out was pretty amazing–with a sense of something magnificent coming to an end combined with the buzz of small talk about what people planned to do next.

All in all–I discovered that tourist time has its own identity, one that is at once separate from and folded into religious time and historical time. Perhaps they merged in this production, in which Shakespeare himself tried to recreate a lost past–a time before England experienced Christianity–even as scholars have seen this play as commenting on monarchical crises in seventeenth century England.

Save

Save